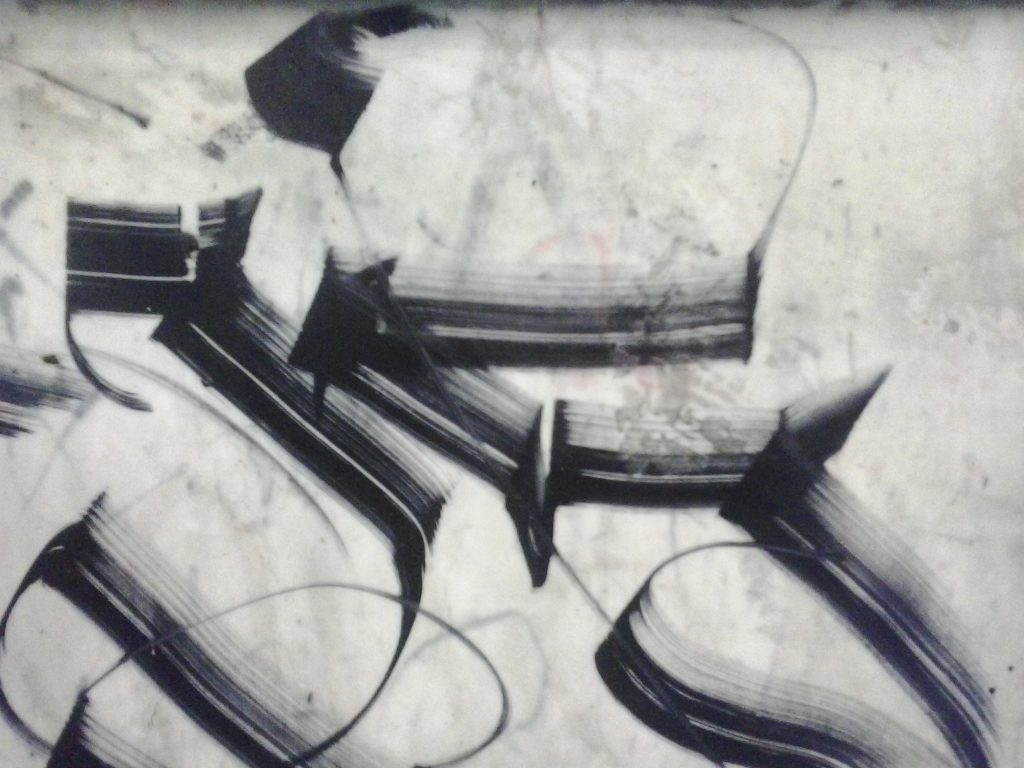

Variations on a simple sentence

“The only link between you and the reader is the sentence you’re making” (Verlyn Klinkenborg, Several Short Sentences About Writing, 2012).

“I have nothing to say, and I am saying it” (John Cage, Silence, 1961).

It is a rather obvious but important fact that writing consists in creating sentences, sentence by sentence, one after the other. While the same might be said of words or paragraphs, it is at the level of the sentence that meaning is primarily produced and messages are made.

The following sentences share a common basis in reality, but by textual variation alone achieve differences in meaning. One sentence might suit a textual occasion more fittingly than another.

Rauschenberg inspired Cage.

Cage Rauschenberg inspired.*

Cage was inspired by Rauschenberg.

As for Rauschenberg, Cage was inspired by him.

It was Rauschenberg that inspired Cage.

What Rauschenberg did was inspire Cage.

* This form while unusual is grammatically correct, and focuses attention on Cage (put in subject position) and the fact that he was inspired (coming at the end of the sentence).

A simple sentence is a single independent clause Subject+Finite Verb(+Object) with no dependent clause – see e.g. Trent Univ.’s page for a quick review of English sentence structures. As the above sample demonstrates, a simple sentence admits surprisingly many variations in English, despite the fact that English word order is more inflexible than in inflected languages such as Czech.

A small lexical variation in inspire/be inspired by – give inspiration to (active)/ be given inspiration by (passive) / find inspiration in (‘active-passive’) – multiplies the possibilities in the above variations on “Rauschenberg inspired Cage”:

Rauschenberg inspired Cage.

Cage Rauschenberg inspired.

Cage was inspired by Rauschenberg.

Rauschenberg gave Cage inspiration.

It was Rauschenberg that inspired Cage.

Rauschenberg it was who inspired Cage.

Cage found inspiration in Rauschenberg.

What Rauschenberg did was inspire Cage.

It was Cage whom Rauschenberg inspired.

Cage it was whom Rauschenberg inspired.

Inspiration is what Rauschenberg gave Cage.

Cage was given inspiration by Rauschenberg.

As for Cage, he was inspired by Rauschenberg.

Rauschenberg was the one who inspired Cage.

As for Rauschenberg, Cage was inspired by him.

What Rauschenberg gave Cage was inspiration.

Inspiration was found by Cage in Rauschenberg.

Inspiration was given by Rauschenberg to Cage.

It was Cage who was inspired by Rauschenberg.

Inspiration is what Cage found in Rauschenberg.

It was Rauschenberg who gave Cage inspiration.

It was inspiration that Rauschenberg gave Cage.

Cage was the one whom Rauschenberg inspired.

It was Rauschenberg by whom Cage was inspired.

As for Rauschenberg, Cage found inspiration in him.

It was Cage who found inspiration in Rauschenberg.

It was inspiration that Cage found in Rauschenberg.

It was Rauschenberg whom Cage found inspiration in.

Rauschenberg it was in whom Cage found inspiration.

It was Rauschenberg in whom Cage found inspiration.

Rauschenberg was the one who gave Cage inspiration.

Cage it was who was given inspiration by Rauschenberg.

Cage was the one who found inspiration in Rauschenberg.

Cage was the one who was given inspiration by Rauschenberg.

Likewise, we can play this game of variations with “Seeing Rauschenberg’s White Paintings inspired composer John Cage,” going to “Composer John Cage was inspired by seeing Rauschenberg’s White Paintings” etc.

Or from “Seeing Rauschenberg’s White Paintings inspired composer John Cage to fully explore silence in his own work” (in which the theme [point of departure] is the encounter with R.’s work) to “It was seeing Rauschenberg’s White Paintings that inspired composer John Cage to fully explore silence in his own work” (the “it” cleft placing emphasis on the encounter with R.’s work being crucial to this development in C.’s work) or to “Composer John Cage found inspiration in Rauschenberg’s White Paintings to fully explore silence in his own work” (pushing the balance toward Cage’s active use of this encounter – the subject and theme is now Cage).

The sentence “Nevertheless, it was the spirited innovation of the painter that most closely influenced the composer” is a cleft form of “The spirited innovation of the painter influenced the composer the most closely,” the “it” cleft and contrastive “nevertheless” putting greater emphasis on Rauschenberg’s spirited innovation being the key factor.

Sources

[1] Lock, G, 1996, Functional English Grammar, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Chapter 11)

[2] Theme and Rheme (ELT Concourse teacher training). This post is with a nod to this page’s variations on “Peter helped Jane”.

Leave a Reply