Searching with Ludwig

Ludwig Guru advertises itself as a search engine that “helps you write better English by giving you contextualized examples taken from reliable sources.”

Free registration (e.g. through Google or with your email address) gives you access over a 24-hour period to 6 Queries and up to 15 Search Results per query, plus the use of some advanced search options (missing word, compare frequency etc.). You can use Ludwig within your web browser or download it as a stand-alone App.

Sources are used that are likely to have been written by or checked by a native English speaker, such as (according to a random sample of those I have seen) online newspapers The New York Times and the Guardian, magazines such as the Economist and New Yorker, BBC websites, Wikipedia, and PubMed. It is a moot point as to how thoroughly scientific articles are checked for English, to judge from some of the sentences to be found in the corpus; there are sometimes also lacunae in sentences from scientific sources caused by the text processor skipping a fragment of the text that is set in an equation environment (“Thus we see that ending the proof”).

The Ludwig Guru homepage gives examples of how you can use the database to

(1) find a word or phrase in context

(2) translate into English from your own language: translations are placed in real contexts, helping decide if the automatic translation makes sense

(3) find definitions, synonyms and examples

(4) compare the frequency of words and phrases

(5) fill in a missing word

(6) paraphrase a sentence

(7) compare the frequency of single words

(8) put a group of words into correct English word order

Let’s take these one by one.

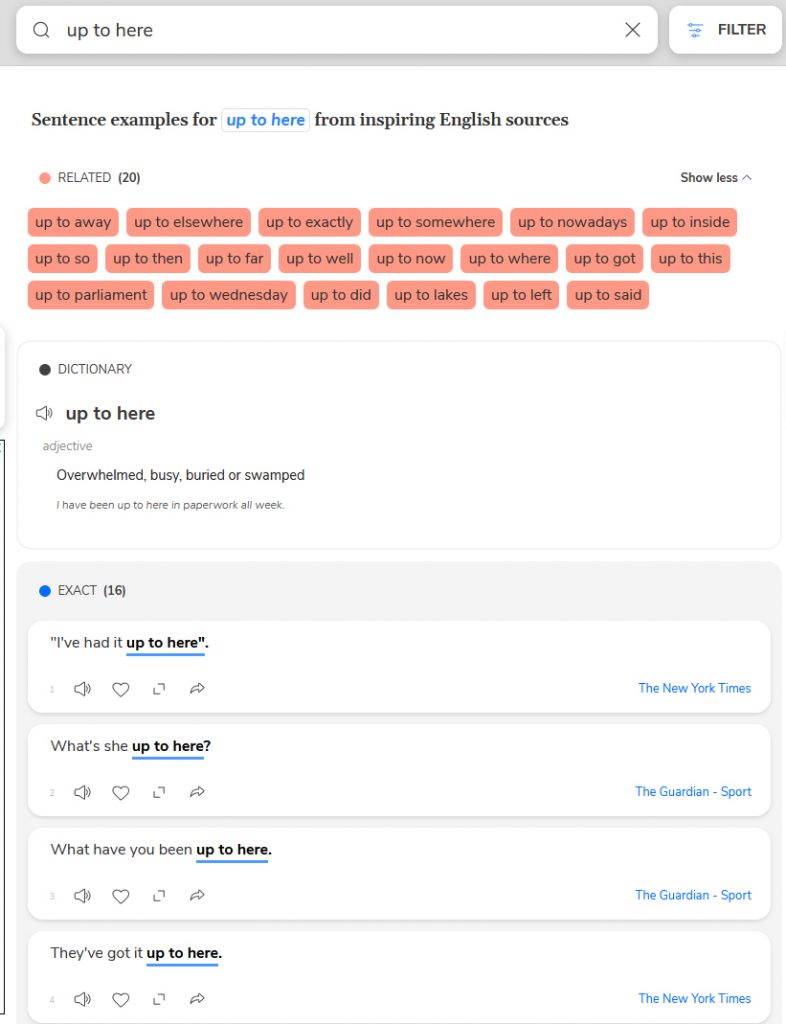

(1) Searching for the idiom “up to here” as in “had enough” gives a dictionary definition and 16 exact matches in the corpus of texts, for each giving the full sentence in which it appears. As well as the sought after idiom as given in the dictionary definition, other meanings are possible that are not listed. For example, the sentence “What’s she up to here?” combines “to be up to” (be doing something) and “here”, producing a different meaning to the displayed definition of being overwhelmed. In other words, the examples give all sentences with the given combination of words, with no regard for whether the contextual meaning coincides with the definition(s) offered.

Also listed are “related” phrases, by which is meant combinations of words obtained from the given phrase by changing one of the “content” words (in this case “here”): these related phrases are largely speaking not collocations in the way that “up to here” is, just consecutive words in a sentence (e.g. “up to did” appears in the sentence “Most of the people he went up to did the usual thing…” and 3 other places in the corpus).

By clicking icon between the heart (save) and arrow (share) the wider context of the sentence is given, which here can be helpful to resolve doubts about the meaning that may linger from reading the sentence alone.

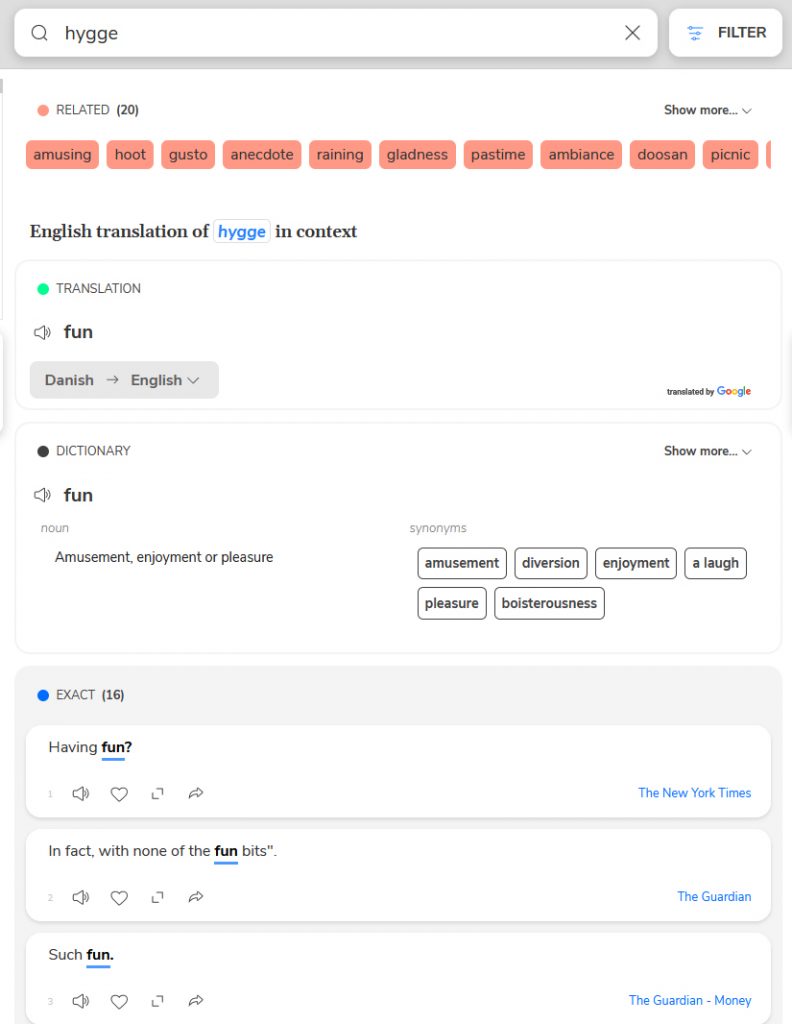

(2) The Danish word “hygge”, which a few years ago spread its candle-fire around every British hearth, and has been accepted if not adopted into English is, according to Lexico online dictionary “a quality of cosiness and comfortable conviviality that engenders a feeling of contentment or well-being (regarded as a defining characteristic of Danish culture).”

Upon typing in “hygge” into Ludwig’s search box, the word is successfully recognized as Danish (the drop-down menu allows a change of source language in case of need), but receives the misleading translation of “fun” (the first offered by Google Translate – the closer “cosy” is next in line) and an array of puzzling words deemed to be “related” – clicking on “doosan” reveals the South Korean conglomerate Doosan, maker of heavy construction equipment, that is in some context must be apparently “fun”, thus providing the connection to “hygge”).

Conclusion: the automatic translation offered by Ludwig (fed from Google Translate) does not make sense. But then to proceed an alternative translation needs to be found, and for that a different resource is needed. So I would use this other resource at the outset to obtain a set of possible translations, and then use Ludwig with the offered English translations as in (1) to check contexts in which these translations occur. Indeed, this is what one of the founders of Ludwig suggests: “People can get their translations on Google Translate, and then check on Ludwig whether or not their translations are correct.”

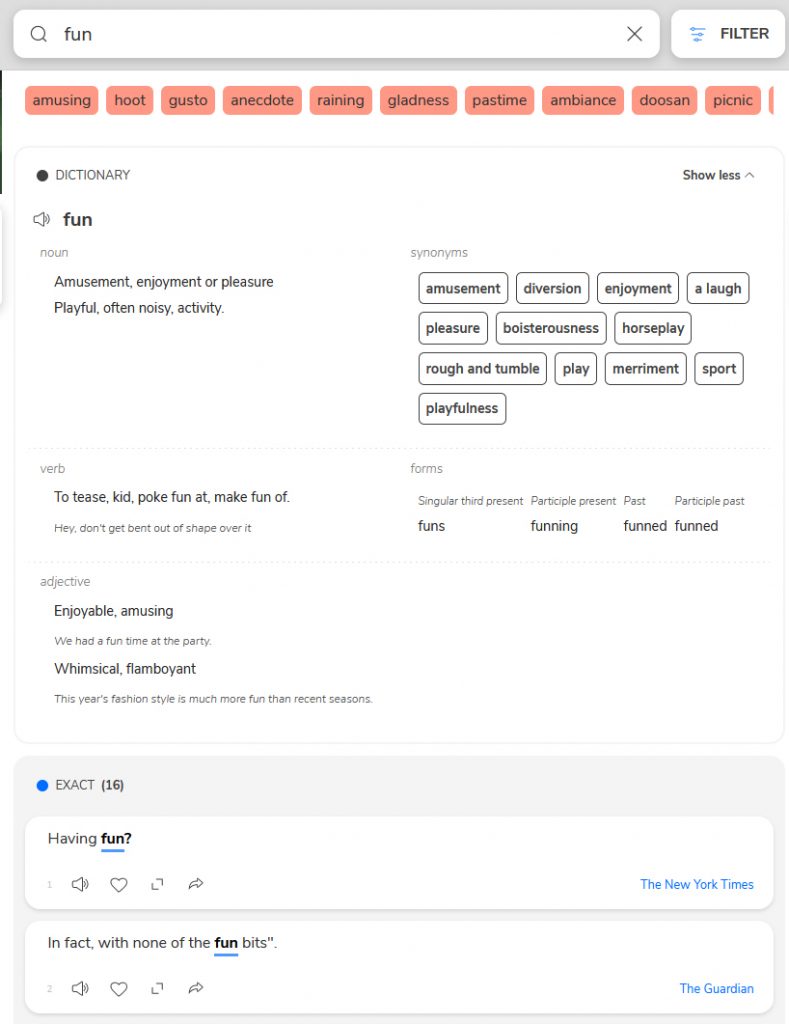

(3) When searching for a word, a dictionary definition alongside synonyms for the word as defined are given ahead of the list of contextual examples from the corpus. This definition is convenient to have at hand so that you do not need to go Google, Lexico (keyed into Google Search), Merriam Webster etc. and is easy to ‘browse’. The dictionary-thesaurus format and detail is similar to Lexico, but is different, even from the “Google-powered” translation used in (2) above. As can be seen for the entry for “fun” – a red herring from “hygge” in (2) above – there is a lack of distinction of register, with the verb form “to fun” given an entry in which not only the example offered does not contain the word (“Hey, don’t get bent out of shape over it” – presumably what follows might have been “I was only funning”) but that “to fun” is informal American English is not indicated. A related point is that distinctions between British English and American English are not made: sometimes you can infer it from the source, but this relies on knowing there is a distinction in the first place…

(4) A vexed question of punctuation, at least among the punctilious, and certainly among the pedantic, is whether to hyphenate such locutions as “well known” and “well defined”. One school of thought – to which I occasionally but unsystematically subscribe – is that when used as a premodifier the hyphen is used, while as a postmodifier the hyphen is not used: thus “A well-defined function” vs. “The function is not well defined.” I sometimes convince myself that the hyphen in the premodifier helps the reader perceive the adjective more readily as a unit; however, as an adverb modifying an adjective does not require a hyphen, in neither case is a hyphen in fact needed: I would not write “A clearly-defined notion” with the hyphen, so I should not write “A well-defined notion” with a hyphen either.

Entering “well defined VS well-defined” in the Ludwig search box, two separate lists show roughly the same frequency of use (even though the summary bar claims 100% for the unhyphenated and 0% for the hyphenated version) and the examples are in line with my own usage pattern (hyphens when placed before the noun modified but not when after) and that hyphen-usage varies even in the same source (e.g. New York Times).

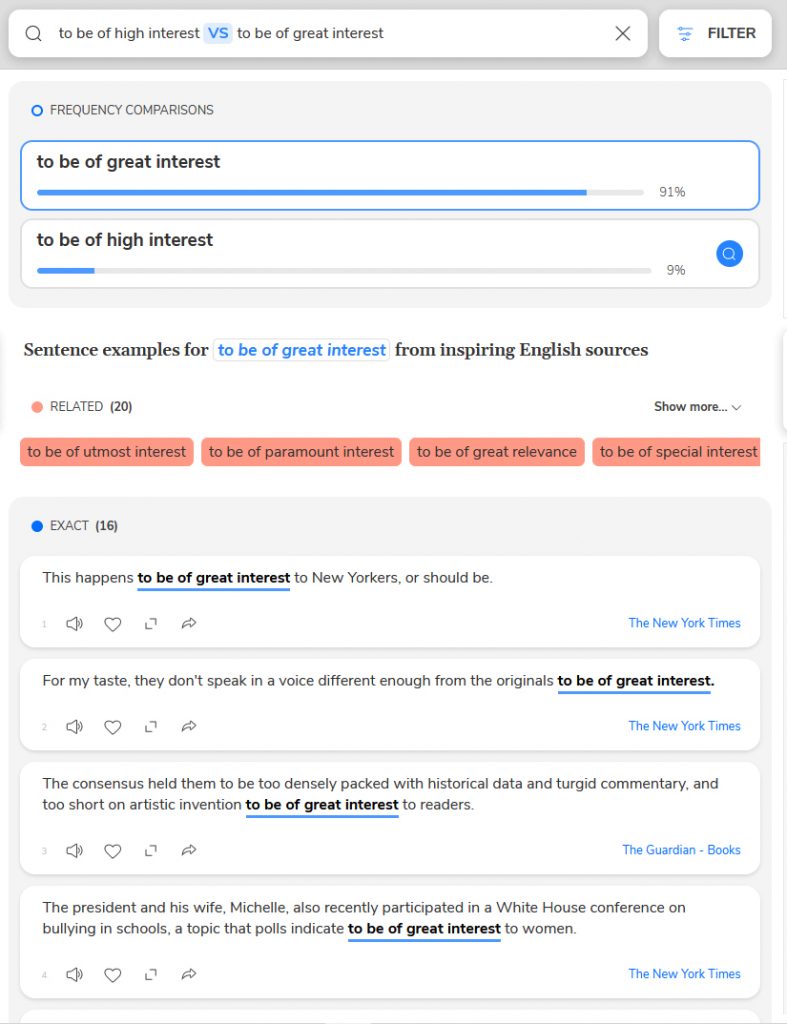

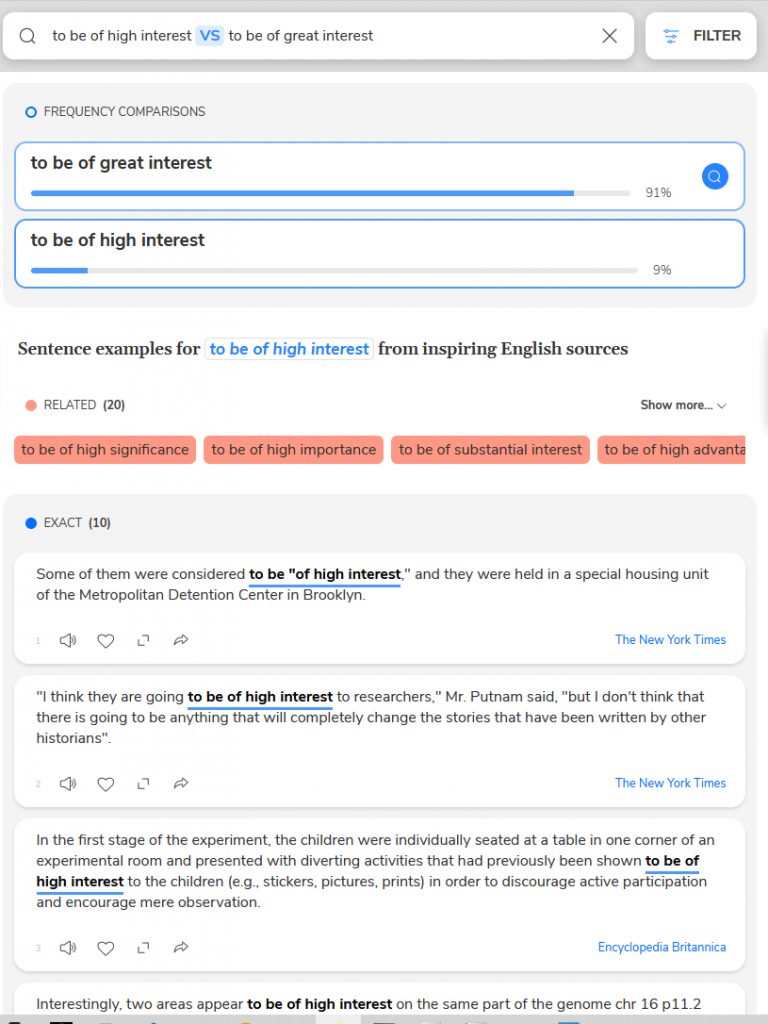

Here is another example of comparing frequencies to check up on a phrase. Upon reading “of high interest” in a student paper, my instinct was to change it to “of great interest” (“high interest” has a tendency, for me at least, to slide into the sense it has in “high interest rate”). Lacking justification for my preference, to check my instinct I entered “to be of high interest vs. to be of great interest” in the search bar, and saw that from the corpus mined by Ludwig the relative proportion of usage is roughly 10:1. Given the not infrequent use “of high interest”, I was able to correct my impulse to “correct” the phrase: its proximity to the collocation “heightened interest” may help accommodate it into my own usage. Such conventions of usage are harmless to ‘violate’ in any event, and may, as in this instance, be merely a personal or local convention: I would say something is “highly advantageous” but not “of high advantage”, “of great importance” but not “of high importance”. Neither rhyme nor reason is to be sought in such predilections.

(5)

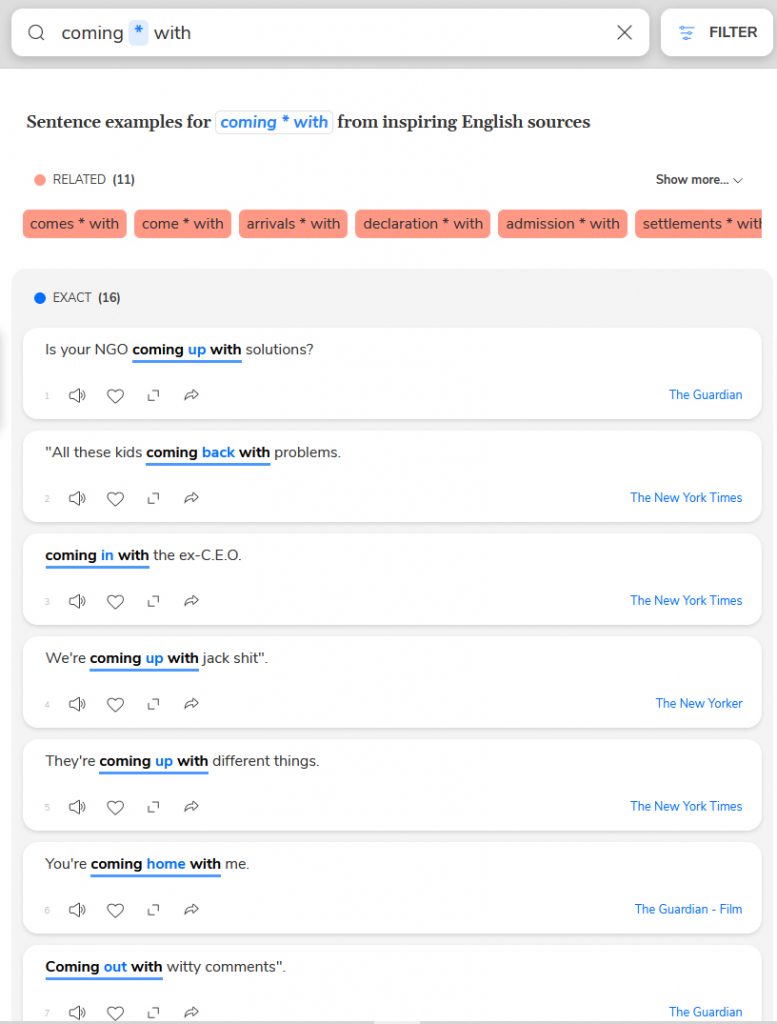

Entering “come * with”, in which * could for instance be “up” (“come up with” = produce something, especially when pressured or challenged) or “out” (“come out with” = say something in a sudden, rude, or incautious way), surprisingly yields only sentences containing the verb-preposition combination “come with” (i.e. the * is not replaced by any word). The ‘related’ phrases listed by Ludwig are proximate only by word substitutions (“communicated * with”), and these substitutions need not be of the same grammatical category (“sources * with”). Some of the related phrases listed are useful, though, such as “coming * with”, which happens to produce a helpful cluster of variants when used as a search term, as shown in the screenshot.

Searches only return exact matches and not derived variants (such as “comes * with” instead of “come * with” – although “comes * with” fares no better in producing collocations other than “comes with” itself). So it can take a number of related searches in order to get what you are looking for – which is not helpful if you are unsure what you are looking for… (Add to this the limited number of searches for the free version of the resource.)

(6) By ‘paraphrasing’ a sentence is meant replacing a word by a synonym. Put an underscore before the word to replace. As in (5), there may be duds: “an _interesting idea” produces only examples with “an interesting idea”. Perhaps this was too testing an example.

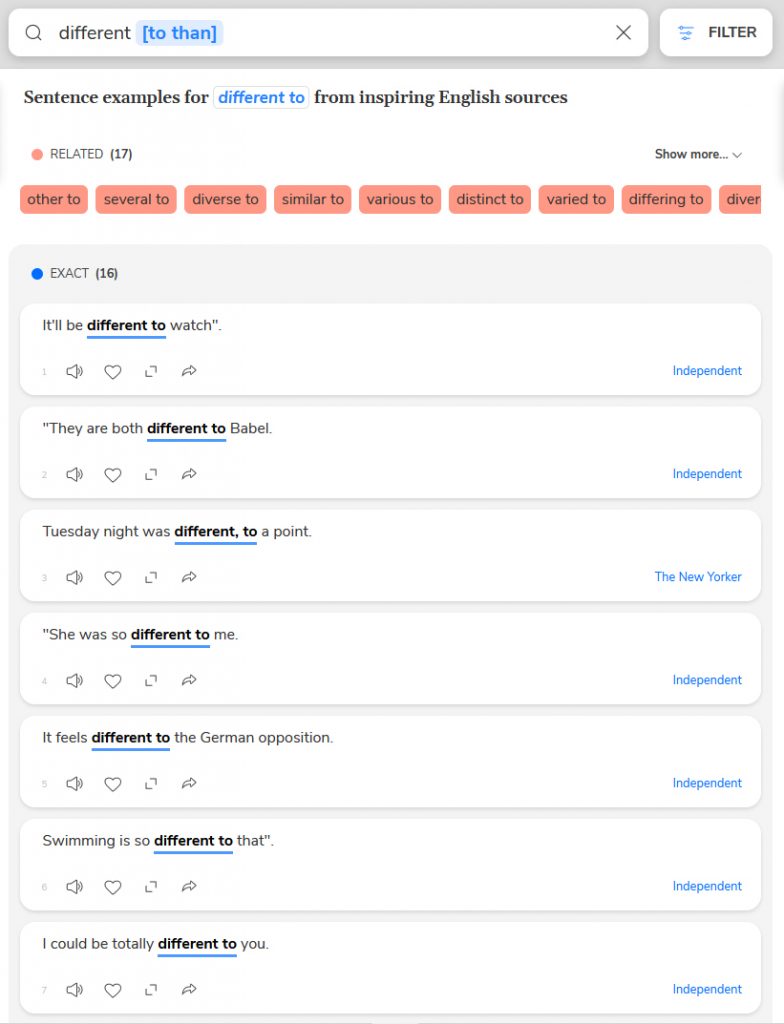

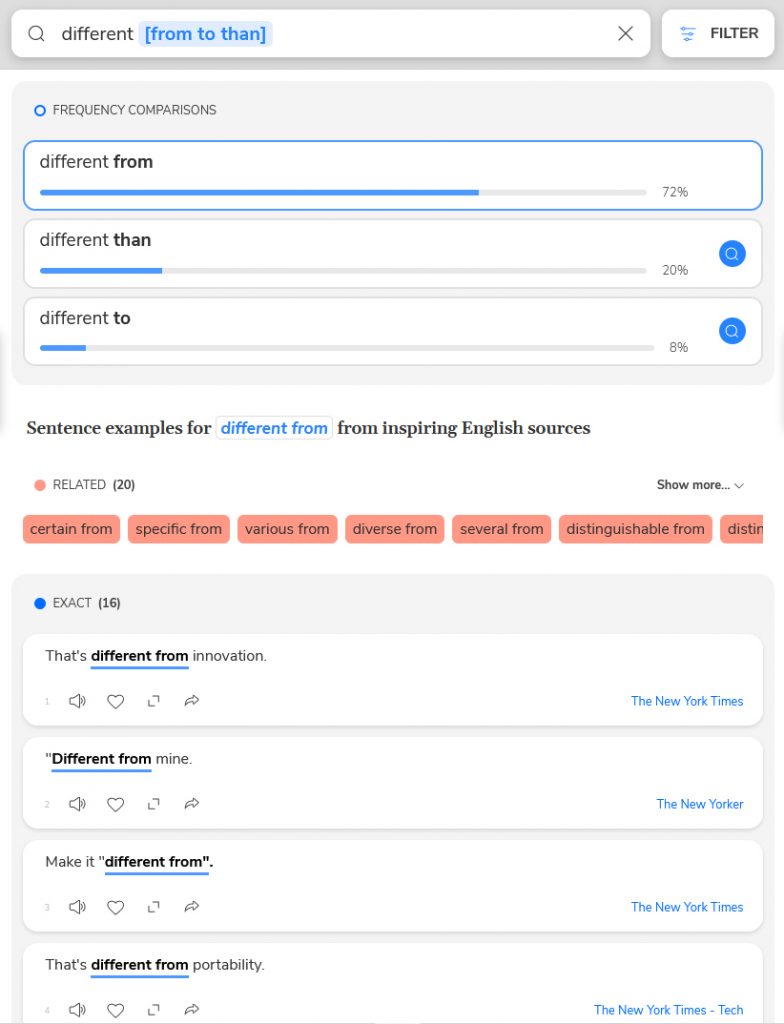

(7) Comparing the frequency of words is a special case of item (4), which allows phrases. Perhaps I vacillate over whether I should say “different to” or “different than” (being British, the former is very much an option; an American leans to the latter). Searching for “different [to than]” in the corpus used by Ludwig, the proportion is roughly 3:1 in favour of “different than”. I can throw “from” into the mix, and search for “different [from to than]”, which shows “different from” to be predominant, appearing almost 3 times as often as the other two put together. Perhaps some “rules” might be guessed by looking at the examples: Merriam Webster has some wise words on the matter here.

(8) Putting a set of words in braces { } produces a search for all permutations of the words appearing in the corpus, giving relative frequencies of them. Perhaps this could be useful in checking the order of words in a binomial (“fast and furious”, not “furious and fast”) or the order of adjectives before a noun: if I enter “{green friendly}”, just over half the appearances are “green friendly”, the majority of which are “green-friendly” as in beneficial to the environment; just under half are “friendly green”, which, in addition to carrying this environmental sense of ‘green’ (“friendly green products”), appears an attribute of a dinosaur and a robot, but not of the giant I was looking for.

Searches of this type allowing any order to the entered words could I suppose also be used to get several searches for the price of one. But the questionable utility of such searches points again to the shaky foundation to Ludwig Guru as a language resource in taking words alone as the basic unit, without any grouping together of inflected forms of a word, and taking sentences as just an ordered sequence of words. Many phrases listed as related to a given search are just combinations of words that happen to be found juxtaposed in a sentence, not units of meaning in themselves (so hardly phrases as such). Again, distinguishing those that are collocations and those that are coincidental combinations relies on prior knowledge.

Verdict: You will occasionally find Ludwig when searching on Google for usage of English words and collocations, but may after a dalliance with Ludwig wish to search for alternatives (and be forced to do so if you use the free version!).

An informative report on Ludwig Guru is given in Julie Moore’s Lexicoblog review of Ludwig Guru (an alternative to Ludwig Guru for academic users recommended here is Sketch Engine).

7 responses to “Searching with Ludwig”

-

I like ludwig but it’s very expensive. You can use lengusa as a free alternative.

Internet should be free and accessible for everyone, and should not stay behind paywalls and subscriptions.World is unfair enough so let’s try to keep the internet as open as possible.

-

Thanks for the pointer to lengusa – and yes walls are unneeded obstacles to opening the doors of communication!

-

-

Ludwig is very nice but I don’t like how expensive it is. Many people learning English cannot afford a monthly subscription (me!). I switched to Sentence Stack.

-

Thanks for the tip on the free resource, Sentence Stack (https://sentencestack.com/) – I shall take a look at it and hope to write about it on these pages in the near future.

-

I had the same problem but I use lengusa instead of sentencestack. It has Wordnet (a lexical database by Princeton University) functionality and only uses high-quality sources. Both are more or less good I guess.

-

Thanks for the pointer to lengusa – I’ll look into this along with sentencestack and hope to write on them here in the not distant future..

-

Dear Andrew,

Thank you for checking up on Ludwig!

I´ve had my doubts but then, not being a native English speaker, it´s sometimes very difficult to avoid a mésalliance 🙂

Kind regards,

Kamila

Leave a Reply